It wasn’t that Disney executives were nervous, exactly. True, the most recent Winnie the Pooh film (the 2011 one) had bombed, but Winnie the Pooh merchandise was still selling, and the film still had a chance to earn back its costs through DVD and Blu-Ray sales. Tangled and Wreck-It-Ralph had both been box office hits, and the Disney Princess franchise was a wild success with small girls.

Still, since the next upcoming film was a severely behind schedule princess film that Disney had been struggling with for decades, maybe—just maybe—it wouldn’t be a bad idea for the animation studio to release a film aimed at boys. Luckily, the animation studio just happened to have another franchise on hand—the recently acquired Marvel Studios. The popular Marvel characters, of course, were already licensed to other studios, or would shortly be sucked into the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but Disney CEO Bob Iger felt that the Disney animation studio could exploit some of the lesser known characters. As it turned out, the Marvel Cinematic Universe would also be exploiting some of the lesser known characters, but fortunately enough, the Marvel Comics universe is large, and after flipping through a number of comics, animators found something the live action films had no plans to touch: Big Hero 6, a Japanese superhero team created by Steven Seagle and Duncan Rouleau, with additional characters created by Chris Claremont and David Nakayama for the team’s later five issue miniseries.

Having found Big Hero 6, the story developers proceeded to almost completely ignore the comic. One of the three screenwriters never even read it.

Almost completely. A few elements, such as character names and Honey Lemon using a purse, were retained, and in keeping with Marvel tradition, a post credits scene featuring Stan Lee was added at the very last minute, when the filmmakers realized that audiences would be expecting both. Otherwise, animators pretty much ignored the other Marvel films, making Big Hero 6 notably not part of the rest of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Not only do other Marvel characters go completely unmentioned, but—contrary to Marvel tradition—the film takes place not in the real world of New York, Miami, London and wherever the Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. feel like bringing questionable science to next, but in San Fransokyo, a sort of alternate universe mingling of Tokyo and San Francisco, with San Francisco’s hills and Tokyo’s buildings. That creative choice allowed filmmakers to blend a sorta present day culture with very futuristic tech, and had the added advantage of just looking really cool.

That tech focus also allowed filmmakers to make one huge change to the original comic characters: none of the human characters have any superpowers. That was true for many of the characters in the comics originally as well, but in the film, even the characters with superpowers in the comics had their innate powers eliminated. Instead, the characters use high tech devices to fly, go zipping around on amazing wheels, shoot out goo, and fight huge robots. The robots, too, were changed. Big Hero 6 does stay with the original idea that robot Baymax was at least in part the work of young robotics expert Hiro, but in the film, Baymax was initially built and designed by Hiro’s older brother Tadashi. And Baymax, more or less a bodyguard in the comics, was transformed into a friendly medical assistant for—spoilers!—most of the film.

In the process, Baymax became the breakout star of the film. His ongoing insistence on seeing everything through the narrow lens of providing medical advice is not just hilarious, but touching. The animators also had fun with scenes where Baymax suddenly deflates or runs out of battery or is equipped with body armor—armor that the robot does not think exactly fits with his health care mandate. Eventually, Hiro’s tinkering even allows Baymax to fly, allowing the filmmakers to create glorious sweeping shots of Hiro soaring through the skies over San Fransokyo.

The other breakout star of the film, for Disney at least, was something that many viewers might not have even noticed: Hyperion, a new program for rendering—that is, creating the final look for the film. Hyperion worked by calculating how the light would move in any given scene, thus letting the computer program know exactly what shade to use for the final coloring. Disney had, of course, played with light effects and studied how light would fall on objects since before Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but Hyperion tried something new: light effects from multiple sources, and calculations of how light would bounce off objects and shift when characters moved in front of it. The result was the most realistic looking backgrounds and objects yet seen in computer animation. It was, on a technical basis, astonishing, ground-breaking, arguably one of the greatest developments in Disney animation since the CAPS system—

And, on a hardware level, very unwieldy. Hyperion was so amazing that it required Disney to assemble a brand new supercomputer cluster, plus a backup storage system which was described to me in technical terms as “very big, no, really big.”

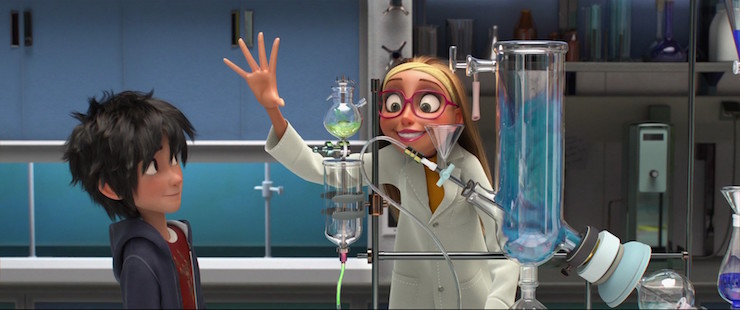

(If you want to see how Hyperion works, more or less, Disney Animation has a little demo up on its website, where you can see how the colors and light shift as Honey Lemon moves through a scene.)

The final result was something that was not exactly a Marvel Cinematic Universe film, but also not exactly a traditional Disney Animated Classics film. Oh, sure, the film plays with some familiar themes from previous Disney animated films—a character who is an orphan, the importance of found families and friends, the dangers of judging by appearances. And the training montage is somewhat reminiscent of scenes from Hercules and Mulan. But none of those themes are precisely exclusive to Disney animated films, and Big Hero 6 contains some profound differences from “classic” Disney animated films. It contains barely a whiff of romance, for instance, even though several of its characters are the right age for it. It lacks adorable sidekicks, although both Baymax and Fred, the slacker fascinated by superheroes and costumes, provide needed comedy moments. Nobody sings. And in a genuine switch from all previous Disney animated films, the protagonist’s initial goal is to get into a school.

In his defense, it’s a really awesome school with amazing tech stuff; also, as a grown-up, I thoroughly approve of the pro-education message, and specifically, the pro-science education message. Even if that message is slightly tainted by later events of the film, but hey, kids, if you focus on your math homework, you too can end up nearly dying, getting sucked into an alternative dimension, and creating massive levels of destruction! Don’t trust me? Trust this film! Would Disney lie to you? Well….ok, would Disney lie to you about this? Let’s not get into this. Go math!

Hiro’s second goal is a more typical one: revenge. But here, Big Hero 6 also takes a different route, because the last two thirds of the film are not just about Hiro’s transformation from robot obsessed kid to superhero, but about the growth of a superhero team. It’s not that earlier Disney films—particularly The Rescuers films—had lacked teamwork, but Big Hero 6 is one of the few to give us training montages for an entire group of wannabe superheroes. Emotionally, this training may center on Hiro and Baymax, but the other team members—GoGo, Wasabi, Honey Lemon, and Fred—have their moments as well, in an echo of other superhero team films (particularly X-Men: First Class), making Big Hero 6 less a classic Disney film and more a classic superhero film.

And a pretty good superhero film at that. Sure, the reveal of the real villain is probably not going to surprise older viewers, and apart from the focus on education, and a team that shows considerably more racial diversity than either The Avengers or X-Men (two whites, one black, two Asians, one robot) there’s nothing really all that new here. As in all superhero team origin stories, the group comes together to take down a threat, with hijinks, jokes and massive stunt action sequences—although since this is an animated film, not a live action one, I guess the phrase “stunt action sequence” is wrong, and I should be using just “action sequence” instead. As in many superhero origin stories, they are inspired in part by the death of a relative/friend. (In this case, a guy is fridged instead of a woman, but similar principle.) A number of the action sequences take place at night. And—spoiler—they defeat the bad guy, yay!

But a few tweaks also help to make Big Hero 6 a bit more than a run of the mill superhero film. The way Big Hero 6 plays with the “billionaire by day, crime fighter by night,” trope, for instance: the film’s billionaire is no Bruce Wayne or Tony Stark on any level. The way Wasabi, working more or less as an audience surrogate, protests several plot developments. The way, thanks to the Hyperion rendering, several action scenes manage to look more grounded and believable than their live action counterparts.

And perhaps above all, Baymax’s ongoing programmed insistence that he’s really only doing all of this to lift Hiro out of a clinical depression—”this” including wearing body armor, getting programmed with several fighting moves, flying, and helping to take down evil supervillains. I’m not at all sure this is a proper, let alone medically approved, therapy for clinical depression, but it’s hilarious to watch, anyway.

Also, the cat. Who is not in the film much, but helps to steal every scene he is in.

Do I have quibbles? By this time in this Read-Watch, it should surprise nobody that the answer is “Of course.” I’m less than thrilled that the teleportation portals bear a suspicious resemblance to the gates in Stargate. (To be fair, I have a similar complaint about several other films and television shows with “scientific” teleportation portals.) And speaking of those portals, I realize it’s a science fiction cliché, but I still remain skeptical that anyone could remain alive suspended between them—especially since, in order to rescue her, Hiro and Baymax have to go into that area—and since they are moving, and speaking, and rescuing her, time quite definitely occurs in that suspended portal area, so how, exactly, is she still alive after all of these years? And would a robot primarily focused on the health and safety of his young charge really be willing to fly high into the air with him using still not completely tested technology—especially at those speeds?

But these are quibbles. The film is still quite fun—and benefits, I think, from a complete lack of romance, and a focus instead on friends and building families. Also, robots.

It also marked a bit of a milestone for Disney Animation: Big Hero 6 was their fourth film in a row to earn a PG rating, signifying that at long last, the studio had gone from fighting to outright embracing the rating. The earliest films, of course, had appeared before the MPAA rating system was created, although like all Hollywood films at the time, they were still subject to the Hays code, something Pinocchio barely managed to satisfy and Fantasia only after some of the drawings were sent back to the animators. When the ratings system was introduced in 1968, those earlier films received an automatic “G” as children’s films, a rating the later Disney films continued to receive right up until The Black Cauldron. The MPAA thought that many scenes in The Black Cauldron were too scary for small children, and slapped on a PG rating—something that Disney executives believed help to crash the film.

Animators knew they were creating children’s entertainment, and many even found the challenge of creating scenes that just brushed a PG rating invigorating. But they objected to having to change scenes that they felt were important to the theme of the film—as, for example, a scene of Esmeralda dancing in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which the MPAA felt contained too much nudity for a G rated film. Mulan, too, had difficulty staying under the radar, and Treasure Planet failed completely—and then bombed at the box office. Disney executives worried again.

Wreck-it-Ralph and Tangled, however, miraculously survived that “PG” rating—perhaps because by then, many parents considered a PG rating more or less equivalent to a G rating, perhaps because both Wreck-It-Ralph and Tangled are considerably less terrifying for small children than the supposedly G-rated, Hays approved Pinocchio, Bambi, and Dumbo. The success of Frozen (which earned its PG rating from a single line in one of Anna’s songs, that the filmmakers thought would amuse older children and be completely missed by younger ones) sealed the deal. Animators were not quite given the freedom to create, say, Saw II, but they could safely deal with heavier levels of cartoon violence, and a greater freedom of language.

Big Hero 6 did not quite manage Frozen’s triumph. But it was still a box office success, bringing in $657.8 million worldwide, and garnering numerous awards and nominations, including the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. The Disney product placement machine flew into high gear, releasing the now standard toys, clothing, trading pins, video games and Funko Pops, but also adding something new: a manga based on the film, not the comic. A television show is currently planned to debut in 2017. It was a solid entry for the Walt Disney Animation Studio.

And, since the studio’s next film, Zootopia, was a Disney original, and Moana and Gigantic have yet to be released, it also marks the end of this Read-Watch.

But not the end of these posts! As several posters have requested, we’re following this up with a Disney Watch-Watch, covering the Disney original films, in chronological order.

Next up, Fantasia.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.